Some tips for card management by Moritz Eggert

“Sticheln” is a simple but strangely addictive trick-taking card game. The special trait of this game is that ALL card suits other than the one played are trumps, the highest valued trump will win the trick. Another, even more important trait is that each player takes one of his cards (all players do this at the same time, secretly) and declares this suit his “pain” colour. This means that all tricks that include cards of his pain colour taken as a trick during the game count as negative point values (in the value of the card, so a “pain” 14 will hurt you a lot! And yes, of course there can be several of your pain cards in the trick!). The cards of other suits in a trick count as only 1 positive point, regardless of the card value, so avoiding tricks is the main issue here.

It will be clear to everyone that earning negative points will be easier than making positive points, so good card management and well-executed play make the day in this “more-difficult-than-it-sounds” game...

Here are some approved strategic tips:

- Selecting your pain-colour

The rules state correctly that it is not good to select a “short” colour as your pain colour. I’d say that 3 cards is the absolute minimum for your pain colour. Of course you want to take a suit that is rich in low cards (the lowest card you play at the beginning as the “pain” card will already count in negative points, so you don’t want to select a set that has, say, a “5” as the lowest card). And you DO want to have your pain colour available throughout the game. A mistake that players commonly do is getting rid of your pain cards as quickly as possible. This will leave you in dire straits if your fellow players suddenly decide to play a round consisting only of your pain suit, where even the meekest card of another suit will take the trick with the “always trump” rule. You want to have a lower card of your pain colour available in this case to “undercut” the suit, don’t you think?

Take the longest possible suit that has the lowest possible cards in average. One or two high cards won’t hurt you, you might just be able to get away even with a “14” late in the game, if you play carefully.

If the suit is too long, you might end up being the only one with that particilar pain suit, and that is not always good. Still, it has it’s advantages, as the other players might quickly use up your high pain suit cards to get tricks. I think it is good to have the knowledge of at least one high card in your pain suit early on, this will make your end game easier (see below).

- Knowing your (pain) suit

And we don’t mean your tailor...Know your suit – at ALL costs. Memorize all the cards that are missing, deducted from the info you have on your own pain cards. You might make a mental note like: “ok, I know 2,3,4,6,9,11,13 of my pain suit are still in the game”. If the “2” is played, scratch it, and memorize the rest, again! Always momorize which cards are still left. Constantly know which cards of your pain suit are still in the game!

I leave it to you to devise your own memory tricks to achieve this, but believe me, knowing the cards left exactly will improve your game 100%. Why? See “The end game” below....

And now to the tactics:

If you have to play your pain card early in the game

So your first, huh? What card do you play? If you have a long suit of your pain card, you might want to get rid of some (the constant challenge in “Sticheln” is: you never want to have too many pain cards, but also not too few). It is clear that you MUST play a low card, to avoid other players forcing awful pain cards on you immediately (and believe me, they will have them readily available in abundance in the first rounds). The highest value you can play depends on the number of players. With 4 players you should play a “2” maximum, for example. A “3” might be dangerous already (imagine the other players playing a 1 and a 2 plus a zero, you will end up with minus 2 points!). Of course your possibilities will improve when you know exactly what cards are left of your pain suit. 5,4,3,1,0 are gone? Of course you can play a 6 then!

I have seen disastrous plays in which the players thought: hey, the chances are really LOW that the others will play this and that card, so I can get away with playing this and that card....DON’T! Murphy’s Law applies here throughout: always assume the worst can happen and make the safest play possible!

- The early game

Again, again, and again: Always make the safest play possible! Make the play that has the least chance of earning you pain cards. You will most likely always have this choice. The game is not won by many tricks, but by one or two safe tricks during the end of the game (and the occasional “Round End” trick taken by the player who comes last in the round, when one can fully judge what cards one will get and how). Follow this rule until you know that all the pain cards of your suit are gone or in your hand, period. If a trick comes along that is absolutely safe to take, take it of course, but with the least effort possible. Wait, wait, wait, and the win will be yours. You might even push this end game in “forcing” a pain suit play. For example: you play an 8 in your pain suit, and you know the only lower cards left in your pain suit are 6 and 4. The other players will happily play these cards in an attempt to give you negative points, but one of them (if you play with at least 3 other players) will just HAVE to play the trump card and gain the trick. Voilà – problem solved. Now you will dominate!

- What card do I play?

Follow these guidelines:

-

you want to have as many suits available as possible, to be always able to “undercut” and avoid taking tricks you don’t want. Having as many suits as possible in your hand means you can always avoid the nasty trick by playing the suit of the first played card. So play all suits equally, always keeping them equally distributed in your hand. If you have only two cards left in a suit, play the higher card – just to be on the safe side. Even if you don’t take a single trick in the game, you will be on the winning side with 0 victory points, especially if you play a series of games.

-

play the middle card of a suit, after deciding which suit to play. Why? You win the game by playing either low cards (avoiding tricks), or high cards (taking tricks when it’s safe). So you want high and low cards, not medium cards. Therefore, if you have a 5, a 7, and an 11 to play, play the 7. Always follow this rule and you will win the end game.

-

always keep some cards of your pain suit for the end game. Of course the difference with the pain suit is that you don’t want to keep the high cards, so if you have many of them, get rid of them early on. But the high cards can be handy in playing destructively (if another player has the same pain suit), so this is not always a clear decision. But with the pain suit, you want to have only low cards in the end game. Why is it not dangerous to have pain cards left at the end of the game? It is extremely unlikely that the last tricks played will only contain one suit, because it would involve a mutual secret pact by all players to reserve only one and only this one suit for the end game. Extremely unlikely....Chances are that many colours will be depleted, and therefore cannot be played by everybody anymore. I could write a long statistical essay on this, but I guess you can trust me that normal stochastic laws apply. If you start a round, and you know your trick suit is depleted, you can always play any card of your pain suit, even the highest ones This is usually the best way to get rid of them, especially when you can “force” a play (see above). The other players will not keep track of your pain suit as well as you do, so they will always try in vain to force their pain cards on you, when you smugly know that they can’t hurt you in fact because of the value of the card you played (=”haha, there are only 2 lower cards than this left, and you have to play the trump card, if you want it or not because you are three other players...”)

-

- When to begin the end game?

The perfect end game begins with you having only high cards in many different suits with your pain suit either completely depleted or in your hand. Now you try to take every trick possible. When you then begin a round, your own pain suit cards, now safe, come in handy, as taking a trick is easier when you react, not when you begin a round. So switch: Gain a trick, let somebody else take the next trick, gain a trick again. 1 or 2 tricks will suffice – you’ll win!

Of course there is rarely a perfect end game with only high and low cards, but you can, as described already, force the end game for you with playing your pain suit cards tauntingly. If there is still a “15” out there in your pain suit, don’t fret. You can go pretty high in attempting a trick then, just be carefully not to play a “15” card yourself, so the pain “15” can be used to undercut your own trick.

Full knowledge of the depletion of your pain suit is, as you can imagine, absolute paramount, so I state it again here.

- Make life hard for other players

If you can give negative points to any player – do it! Even if you waste cards you think are valuable later on. Always go for maximum damage, give them the highest card in their pain suit you have! The only difference is when you’re the last one to play a card and could gain a trick with only positive points for you. The other players might groan when you foil their plans, but taking four positive points for yourself means giving ALL the other players negative 4 points (in comparison to you), so that’s ok.

| View/add comment |

And that’s it. Follow these simple rules, and you’ll be much more successful in playing this sometimes very confusing game.

Have fun!

This game has made history - in my own family as well. We played it as long ago as Christmas 1978, that was even before it had won the title "game of the year" - the first winner of this newly instituted award. As evidence of this prehistoric acquaintance you can examine the lid of the box, where the famous Logo is missing.

At that time my 8 year old niece Kerstin had been given the game as a present and had to fight with her hands and her feet (and tears as well) to convince her mother to let her bring the game along to the Christmas visit at her grandparents'. This was the first time that our family circle played the game ... every day ... with ever increasing enthusiasm ... and the game always took new a course ... and was good for surprises ... right up until today.

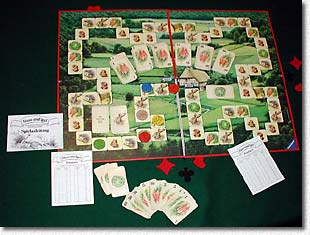

The game is a race which must be run along a given course from a common starting point with the objective of becoming the first to reach the finish. It all takes place without dice - this was in its time a complete novelty in the structure of a game. At his or her turn each player can move as far forward as he wishes, provided that he can afford such a move: each move towards the finish must be paid for in carrots, and these are strictly limited in number. At the same time the price does not increase linearly with the distance, but relates to the square of the number of squares one jumps. The exact formula is:

Price = number of squares times (number of squares + 1) / 2.

Using this formula it can be seen that to move forward one square costs just 1 carrot, but 20 squares cost as many as 210 carrots.

When there are 5 or 6 players each one is issued with 98 carrots as starting capital. No-one can make much progress under these conditions, so everyone is always on the look-out for new sources of carrots.

Wasn't it - in those days of Monopoly millionaires - very daring to try to introduce a game in which trifling numbers of carrots formed the currency? Nor was the underlying ecological principle at all in line with the predominant public opinion of the time. Such views were subscribed to then by at the most an intellectual elite consisting of freaks and anarchists. Even today "old Europe" is fortunately still capable of providing new impulses which can further the cause of humanity, whether this a matter of moderation, or lack of arrogance or in the appropriateness of the means ...

I don't want to describe the rules of the game in

any further detail. I will assume that the reader knows what this game is all about.

There is in addition enough literature on the subject. And anyone who does want to

know more should simply buy a copy of the game. I am prepared to guarantee that this

will be a very wise decision.

I don't want to describe the rules of the game in

any further detail. I will assume that the reader knows what this game is all about.

There is in addition enough literature on the subject. And anyone who does want to

know more should simply buy a copy of the game. I am prepared to guarantee that this

will be a very wise decision.

The outward presentation of the game suggests an image of "child's play". The German name "Hase und Igel", or "Hare and Hedgehog", comes from one of the well loved tales of the Grimm brothers, while the original English title "Hare and Tortoise" refers to one of Aesop's fables. This is less well known in Germany but the story corresponds better to the idea of the game: the course of the race must be run once only, the winner reaches the goal with his own efforts alone and without the aid of trickery; instead he wins by applying his speed to the appropriate extent.

The underlying principle of this game is absolutely a matter of strategy, which requires more planning and foresight than is apparent at the first glance. Brian Bankler writes in his review: "With good players, the game is tense, but predictable." I can not in any way confirm this predictability. Of course there are situations in which the right move is self-evident, and of course there are sequences of moves which are inevitably favourable or unfavourable and call for certain defined tactical measures. What however Bankler recommends as strategic tips, such as:

- use every opportunity to get rid of a lettuce

- pay attention to the order of play ahead of lettuce squares

- your profit in carrots whenever possible

- never let carrots fall into the lap of your rivals

seem to me rather trivial, and following them is a matter of course.

I consider the right choice of speed in the various phases of the game to be much more decisive and strategic. The sequence in which the players begin the game plays an important part here. As the starting player I have no choice but to go straight to the first lettuce square, sit out one round there and, when it's my turn again, to evaluate the moves of the other players. I don't like being the starting player, whatever the number of players. One doesn't earn enough on the first lettuce square, and there also aren't enough lucrative regeneration squares until the second lettuce square and one stays hungry for the duration of the game.

Even as the second player one obtains at least 10 more carrots for the first lettuce square, usually as many as 30 or 40 (I am now assuming there are 6 players), as several competitors - very reasonably - are not going to wait until the lettuce square is free again and move on into the "area of no return", that is, beyond the first tortoise square, from where one can not get back to the first lettuce square.

Starting third is my favourite position. Here I move to one of the first lettuce squares and sit it out there of my own free will until the first and second players have reached and then left the first lettuce square. While waiting I pick up 10 carrots for each missed turn, and when I then give up my lettuce I usually get another 50 or 60 carrots. I have thus more than doubled my original number of carrots, when I hurry after the pack which has pulled ahead by four moves.

Those players who start fourth, fifth or even sixth have to weigh up carefully whether they should still wait for the first lettuce square or whether they should head at once for the second lettuce square by taking advantage of other profitable squares - but there aren't very many of these. Should this succeed, you are now almost broke, and you've got to fall backwards. You gain on the relatively long stretches up to the respective tortoise squares, and while doing this should naturally consider the suitable numbered squares when you are next moving forwards. Above all however you must keep an eye on the second lettuce square which has been left behind, in order to enter this square once more when the order of the players is more favourable, with a considerably higher profit in carrots this time. By this time the other players are scattered more widely around the board, and it is now perhaps possible to get through the back straight fairly economically by exploiting the 2 and 3 squares.

The back straight demands a very well considered approach. Whoever is the first one to pass along it is simply paving the way for the others. There are hardly any squares on which the leader can collect carrots. The pioneer - someone must after all make a start - ought in any case consider dropping back again from the leading position, above all when by doing this he can spoil the chances of the others' picking up the appropriate amounts from the numbered squares.

The third lettuce square marks the beginning of the end-game. If you arrive here soon enough - even with no carrots in your wallet - you can attempt to reach the finish from here by means of short but steady forward moves. Should this lettuce square however be occupied, and some other competitors who are interested in the lettuce have their turns before you, you should not stand around here too long missing turns. It's then better to fall back again to pick up more swing, in order to aim after that at a slightly higher speed for one of the two lettuce squares near the finish. But you must take careful aim: you must have the right number of carrots remaining in your hand! Im Vorfeld sind Zwischenfelder viel besser kalkulierbar als am Ende. Anyone who makes a mistake here and is forced to move to a hare square as an emergency case is in for a nasty surprise. Either with "Your last move cost nothing" or with "You must fall back one position immediately" you have at a stroke lost the lead that you had built up with so much concentrated effort.

There is also a major difficulty with the last lettuce squares: ones competitors can - either by overtaking or by not doing so - alter ones expected reward of carrots. The effect is either that one has either too many carrots and must sit out to get rid of them, or that one has too few and must obtain some more by moving backwards. In both cases one loses 3-4 moves on the way to winning.

In the history of the Westpark-Gamers we have played this game only once, and then without any great sense of purpose. At the time - about one year ago - I had to promote it vigorously. This time it was an emergency solution, as Moritz had brought games with him only for the expected 5 players, but Björn was there as a surprise guest to make 6. So we went through my repertoire of 6 person games and finished up with "Hare and Tortoise" again.

Not exactly to my delight I was the starting player. Naturally I went immediately to the first lettuce square; none of my competitors overtook me and I was not very happy with the 10 carrot reward. By now four players had overtaken me, just enough to make the following free numbered squares hold out little chance of success. The 2 to 4 positions were hopeless and the questionable 1/5/6 flag square a long way off. I moved to a hare square and promptly drew "Miss a turn". In this phase this card is almost fatal: I could say goodbye to the lettuce squares, and goodbye to the main bunch of the competitors.

I let myself drop back to the last tortoise square, improved my finances again a couple of times on the flag squares in the back area of the board, was able to get rid of a lettuce at a good profit on each of the second and third lettuce squares and reached third place without any further setbacks.

Peter was the last player to start. He was also the only one who remained behind me when I ate my first lettuce. (To my dear fellow competitors, in particular to the dear players who started second and third: that was a big mistake on your part, the bitter effects of which you came to feel later!) In this way he earned 60 carrots with his first lettuce, could then leave the next flag square for 50 carrots (missing a turn, I was the only one remaining behind him), had to struggle a bit to dispose of his remaining two lettuce, and was the pioneer on the back straight, for which he got little thanks. Perhaps it was here that he lost his advantage in carrots again - but not completely, for he managed to come in second.

Moritz was the fourth player to enter the race. He somehow chose a deliberately inconspicuous role - but one entirely appropriate to the game. He ate his first lettuce on the second lettuce square He was able to dispose of the second one by drawing the card "Eat a lettuce at once". (This is - regrettably - almost the winning card!) In Peter's wind-shadow - that means cashing in on the 2-squares - he was able to negotiate the back straight. He calculated his run-in exactly and thus won the game.

Deservedly so? Well, to some extent! Suppose for once we exchange your "lettuce" card with my "miss a turn" card. But that is just the envy of the dispossessed ...

One word to the other three also-rans (or better, also-hopped): you also had the honour of taking part! I don't want to add anything else.

| View/add comment |

Nothing to report this time.