This is an earlier effort of Reiner Knizia, a very abstract game of bidding

and trading. It is played in three rounds, each of these rounds is divided into a bidding

and a scoring round. There are 36 cards depicting 5 differently coloured wares in values

0 to 5 (0-1-2-3-4-5-5), and one “neutral card” with the value of 10. In turn,

every player turns over 1, 2 or 3 cards (s/he can decide to turn over additional cards

after seeing what card was turned over). The player to her/his left starts bidding (each

player starts with 30 “gold”). There is only one bidding round, so the last

player in the round (incidentally the card turner) can always make the bid if s/he wants.

The maximum amount of cards you can own is 5, and you can not bid for cards which would

bring your assembled cards to more than 5. This makes for an interesting decision for the

card turner, as s/he can exclude certain players from the bidding by turning over more

cards than they can take!

This is an earlier effort of Reiner Knizia, a very abstract game of bidding

and trading. It is played in three rounds, each of these rounds is divided into a bidding

and a scoring round. There are 36 cards depicting 5 differently coloured wares in values

0 to 5 (0-1-2-3-4-5-5), and one “neutral card” with the value of 10. In turn,

every player turns over 1, 2 or 3 cards (s/he can decide to turn over additional cards

after seeing what card was turned over). The player to her/his left starts bidding (each

player starts with 30 “gold”). There is only one bidding round, so the last

player in the round (incidentally the card turner) can always make the bid if s/he wants.

The maximum amount of cards you can own is 5, and you can not bid for cards which would

bring your assembled cards to more than 5. This makes for an interesting decision for the

card turner, as s/he can exclude certain players from the bidding by turning over more

cards than they can take!

At the end of the round the players count the value of their cards and

get the most money for the highest sum, less money for the second highest and so on. Then

the scoring round begins: Now the colours come into play. Each player advances tokens on

different “ware pyramids”, one step for each card s/he owns at the end of the

bidding round. Again each pyramid brings money after scoring – but only to the two

highest tokens. The “10” card doesn’t move any token at all (but will

assure you profits at the end of the bidding round, which is also important). Who has the

most money after three rounds wins.

At the end of the round the players count the value of their cards and

get the most money for the highest sum, less money for the second highest and so on. Then

the scoring round begins: Now the colours come into play. Each player advances tokens on

different “ware pyramids”, one step for each card s/he owns at the end of the

bidding round. Again each pyramid brings money after scoring – but only to the two

highest tokens. The “10” card doesn’t move any token at all (but will

assure you profits at the end of the bidding round, which is also important). Who has the

most money after three rounds wins.

The dilemma is obvious: Should you collect cards to advance tokens, accepting bad values like “0” and “1”? Or should you concentrate on winning the bidding rounds (which gives, in the short term, more money).? And that’s about it – what we have here is a purely mathematical game, which doesn’t have anything to do with the historically fascinating exploits of the real “Medici”. The game could be called “Grocery Store Empire” or “Chewing Gum – The Game” and would play the same. But well, that wouldn’t sell wouldn’t it?

A capable effort from Germany’s most prolific game designer, that’s all we could say after playing it. It works as a mathematical dilemma, but doesn’t really make for an exciting or colourful game.

Westpark-Gamers score: 5.67

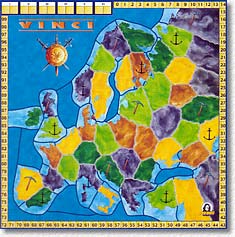

Definitely one of the most successful of the “Euro-Games” line

(surviving atrocious rules translations and counter misprints). The game is like a small

version of “History of the World” – on a relatively small map (for this

kind of games) of Europe various cultures and empires rise and fall, with the goal to

accumulate as many victory points as possible. The Empires are created by an ingenious

random (counters are drawn from a bag) combination of “cultural traits” which

results in immensely various player powers. For example you could have the combination

“galleys” and “mines”. The galleys bring you additional attacking

power when attacking along coast lines, the mines bring you additional victory points

when occupying spaces with a “pickaxe”. Other traits could be

“fortresses” which bring defensive forts, “spies” which give you

the ability to make an especially cheap attack, or “diplomacy” which prevents

one player from attcking you (and you from attacking her/him) each round. The

combinations are virtually limitless. Of course they are not all eqally powerful, which

is partly dealt with by giving the more powerful traits less “people power” -

you see, each counter also determines how many tokens you get when founding the empire

– the more tokens you have, the more expansive power is apparent in an empire (you

need tokens to conquer spaces and to occupy them after conquest).

Definitely one of the most successful of the “Euro-Games” line

(surviving atrocious rules translations and counter misprints). The game is like a small

version of “History of the World” – on a relatively small map (for this

kind of games) of Europe various cultures and empires rise and fall, with the goal to

accumulate as many victory points as possible. The Empires are created by an ingenious

random (counters are drawn from a bag) combination of “cultural traits” which

results in immensely various player powers. For example you could have the combination

“galleys” and “mines”. The galleys bring you additional attacking

power when attacking along coast lines, the mines bring you additional victory points

when occupying spaces with a “pickaxe”. Other traits could be

“fortresses” which bring defensive forts, “spies” which give you

the ability to make an especially cheap attack, or “diplomacy” which prevents

one player from attcking you (and you from attacking her/him) each round. The

combinations are virtually limitless. Of course they are not all eqally powerful, which

is partly dealt with by giving the more powerful traits less “people power” -

you see, each counter also determines how many tokens you get when founding the empire

– the more tokens you have, the more expansive power is apparent in an empire (you

need tokens to conquer spaces and to occupy them after conquest).

But there is an even more ingenious idea: there are always 6 empire

combinations to choose from, the ones that are the “furthest away” cost more

than the “nearer ones”. If you take any empire, the gap is filled by adding

another empire at the topmost position, and moving the others down. Everytime you take

more expensive empires, the point cost you pay is added to the empires “jumped

over”. This means that empires which seemed uninteresting at first become more

attractive later in the game as you will get the accumulated points as a bonus when you

take these “nobody-wants-me” combinations. Playing an empire is easy - you

start somewhere on the rim of the board and try to conquer spaces through combat. The

latter is handled totally deterministic: the number of tokens necessary to conquer a

given space is calculated by taking the number of defending tokens, terrain and special

abilities into account. If you can match that number, you conquer the space – easy!

The problem is you have very few tokens for an empire, and each attack on you will result

in you losing one token permanently. And to get victory points for spaces needs you to

occupy a space with at least one token. This means that most empires “max

out” after 2 or 3 rounds. Any attack after that will always weaken you without you

ever having the chance to build up again. This is when you decide to put your empire into

“decline” to start a new one. The old surviving tokens become passive (like

in “History of the World”), but will give you additional points as long as

they survive.

But there is an even more ingenious idea: there are always 6 empire

combinations to choose from, the ones that are the “furthest away” cost more

than the “nearer ones”. If you take any empire, the gap is filled by adding

another empire at the topmost position, and moving the others down. Everytime you take

more expensive empires, the point cost you pay is added to the empires “jumped

over”. This means that empires which seemed uninteresting at first become more

attractive later in the game as you will get the accumulated points as a bonus when you

take these “nobody-wants-me” combinations. Playing an empire is easy - you

start somewhere on the rim of the board and try to conquer spaces through combat. The

latter is handled totally deterministic: the number of tokens necessary to conquer a

given space is calculated by taking the number of defending tokens, terrain and special

abilities into account. If you can match that number, you conquer the space – easy!

The problem is you have very few tokens for an empire, and each attack on you will result

in you losing one token permanently. And to get victory points for spaces needs you to

occupy a space with at least one token. This means that most empires “max

out” after 2 or 3 rounds. Any attack after that will always weaken you without you

ever having the chance to build up again. This is when you decide to put your empire into

“decline” to start a new one. The old surviving tokens become passive (like

in “History of the World”), but will give you additional points as long as

they survive.

In a normal game you play 2-4 different empires – if a culture survives 4 or 5 rounds it can already be described as being very succesful. In a 6 player game the final round begins when 1 player reaches the score of 100 – the round is played to it's end and the player with the most points wins. This will normally not take longer then 2 hours, and you have seen dozens of empires rise and fall (think of the endless “Civilization” in comparison!).

The game is good, no doubt, the mechanisms work, and it is easily explained and played even with novices. But... and that’s a big “but”, it is one of the WORST “kingmaker games I’ve ever seen. As the scores are open and the moves totally calculable, every player can hurt the position of any player badly, if s/he decides so. If you want to play aggressively against one player because you already lose, you will most probably prevent her/him from winning . At least with our gaming group there is constant bickering about who should attack whom at any given point. It doesn't have to, but it can degenerate into a kind of “bullying” game, in which not the playing style but pure group dynamics decide who will win in the end. Because of this this game has recently taken some flak, and there have been some attempts to remedy this problem (hidden scores, for example).

Still, it is one of the few “grand-style” empire building games, that is playable in a very short time without feeling cheated. If you can bear the fact that the game is totally ahistoric (the empires don't have names, although the combination “farmer/mountaineer” will bring certain Swiss traits to mind, for example) you will be in for a treat.

Westpark Gamers score: 7.5 (lowered)

One of our group commented “he must have a lot of time”

when reading about Martin Wallace's (this game's designer) job as a grammar

school teacher! Well, he certainly designs an impressive number of games – not all

of them winners, but excellent games like “Lords of

Creation” or “Empires of the

Ancient World” come to mind when thinking of Wallace.

One of our group commented “he must have a lot of time”

when reading about Martin Wallace's (this game's designer) job as a grammar

school teacher! Well, he certainly designs an impressive number of games – not all

of them winners, but excellent games like “Lords of

Creation” or “Empires of the

Ancient World” come to mind when thinking of Wallace.

This game is a relatively minor effort of his – a simple “trick-taking” card game of no great inventiveness. 9 cards are dealt out to each player, ranging from 15 (highest) to -10 (lowest). Then one card less (from the same -10 to 15 stack) than the number of players is dealt out openly. Each player now plays one card face down, then the cards are turned over, and the lowest played card takes the lowest open score card (the “trick”). S/he is “out” and greeted by a rule-enforced (!) “... und Tschüss” by the other players (which means “good riddance” in German, well that reminds me of the games I had to endure as a grammar school kid...). In subsequent rounds the sum of the cards played until then is counted, not only the newly played card. Sounds easy and stupid (well it is, a little), but don't forget there is 1 card less than the number of players. You see, there will only be two players left who compete for the last card, and one of them will get... nothing. So it might be more clever to drop out early on and be satisfied with a low card, than to spend lots of cards on nothing.

Cards unused are kept, you fill up to 9, and a new turn begins. The player who dropped out first also has the opportunity to exchange cards s/he doesn't want. After the deck has been exhausted a certain number of times, the player with the highest collection of score cards wins.

If this sounds not particularly exciting you're right. The question is, as there are so many interesting German card games around (think of “6 nimmt!” for example), do we really “need” a half-baked effort like this? Well, Goldsieber seems to think so. Not atrociously bad, but not a winner either.

Westpark Gamers score: 3.0

Again we delved into this favourite of ours – I have already described it abundantly, so let it be said that this game had two “historical events” –

Let me describe the end game of game 1: Aaron and Walter had one dice left each, I had two. We roll, Walter places the die on two “2's”. Hmm... interesting. Aaron shoves the die immediately to three “2's”. Even more interesting! Without hesitating I bid four “2's”, which Walter, as there were no more dice than 4, had to challenge. I had two “2's”, and Walter and Aaron each had a star or a 2! Nice win for me....

The next game was totally wild. It immediately became clear that there were a lot of “5's” around in one particular roll. People kept “saving” 5's outside their dice-shaker and re-rolling. In fact, we ended up placing nearly all of our dice into the open, which moved the “bidding” BEYOND the count printed on the track (which ends at 20). Only when we reached 24, somebody disbelieved (rightfully) the illusion. In my experience this has never happened in a game I know of – any similar experiences out there? A new record?

Westpark Gamers score: 7.58 (lowered, Basti didn't like it that much)